When You Have the Place to Yourself

There couldn’t be a more perfect morning than the one I woke to on a recent Wednesday in early September. The temperature not quite sweatshirt-ready, it dawned crisp and cloudless at 6:30 am on Lake Sebago in Harriman. “You’ll have the whole place to yourself,” the manager of Baker Camp had told me when I checked in the day before. And it was true.

I’d been up for an hour taking pictures before I settled onto the porch, coffee from the JetBoil ready and some instant oatmeal in the pot. A hummingbird, attracted to the Jetboil’s red jacket, buzzed my porch. Crickets sang sweetly all around me while crows argued in the pines. The lake, so close and so blue below me, barely rippled, but threw shivering reflections on the eaves of my little porch. Nothing else stirred.

I’d come here to write a little, to read, and to try to find the perfect nearby getaway in Harriman for someone who is not quite comfortable sleeping outside in the wilderness, unsheltered, alone. At Baker Camp, a 1930s-era group camp on Sebago Lake in Harriman. I found just that. This is not the Baker Camp of summer — a lively, crowded and, to some ears, noisy place that children and adults return to year after year. This is the post-Labor Day experience, when the last campers of summer have left, and Baker becomes another place altogether.

Odds are good that you’ll be the only one on the campground if you book a cabin mid-week. If you’re a writer, a reader, a couple who’d like to escape the city for a night, if you’re having trouble pulling together an escape that stretches over a few days, if you just want to get away for some peace and quiet and the clear air of early autumn, this is your time.

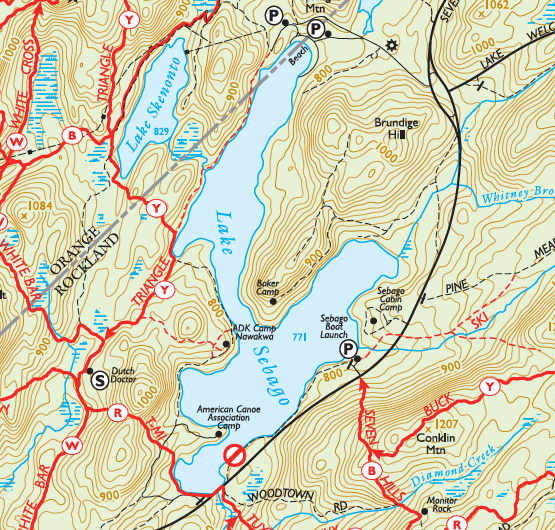

Baker Camp occupies one of the prettiest stretches of Lake Sebago’s curving shoreline. At the end of the Brundige Hill thumb, which divides the lake into two arms, Baker Camp sits alone amid pines and cedars, enjoying views to all parts of the lake. Across the lake and to the east is the Sebago Boat Launch; directly across the narrowest part of the lake is the Adirondack Camp, with the canoe camp to the south, on a little peninsula. All quiet, fall advancing.

The Camp

The three-mile driveway, from Seven Lakes Drive to the camp, follows a snaking route once known in picturesque local usage as the “Mad Dog Road”, all the way to the camp office. In the setting sun, a small herd of young deer was feeding on platters of corn, scattered by the camp managers, when I arrived. We sat there, watching, the manager telling me about the deer family, before I settled up (a sixty-dollar check took care of the rent) and got my instructions.

We talked about bears (“I’m not going to lie to you. We had a bear here, two weeks ago. He tipped over every garbage can.”), the hummingbirds, and then the dangers of being a woman in the woods alone. “I took some real chances, back then”, she recalled. I could tell she loved these woods, the lake that shone up from between the pine trees.

Harriman State Park was built, in large part, to connect children of urban poverty with nature, and the camps that sprung up along the shores of its many lakes offered a respite from city life. But some, like private Baker Camp on Lake Sebago, were built for other purposes; Baker was the project of a mutual corporation of banks as a summer camp for their employees.

Now, you can rent a cabin for $60.00 (standard) from April to October. But for me, the real value comes after Labor Day, when the camps can seem almost abandoned. If you can steal away from work — say, leave a little early on a Tuesday afternoon, call in sick for Wednesday — you can experience a side of Harriman camping that few others know: waking up in an old cabin, alongside a pristine lake, with not another soul around you.

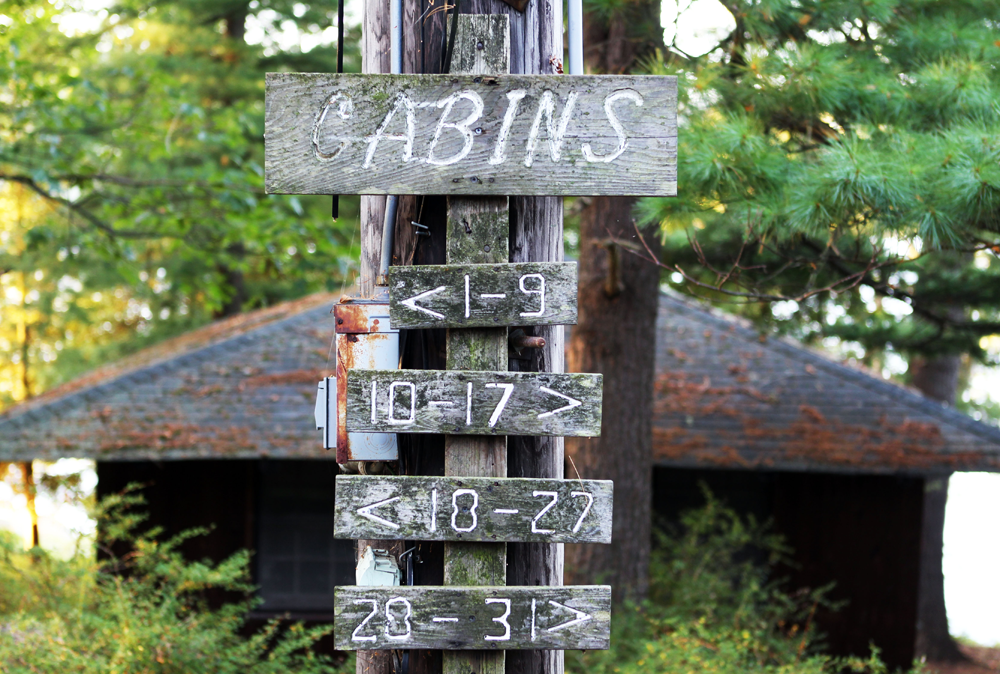

She’d given me 127, a two-room cabin just up the hill from the lake. It sat under the pines and the cedars, logs for stilts holding up the front porch. All the cabins face the water, with the larger ones uphill slightly. They all have porches; they’re all made of rough tree logs and bark, with pine floorboards and a central “trunk” running up the middle. This construction is typical of most of the timber cabins throughout the park: no insulation or running water, and a rickety appearance that makes you think twice about bounding up the porch steps.

I’d half forgotten what a camp is. As a family of seven kids, we’d spent summers at my grandmother’s Adirondack camp, and the basic architecture of that sweet summer place prevails here: the hollow-sounding floorboards, the banging screen door, the dark interior wood that absorbs all the light a single lamp or a bare ceiling light bulb can throw. There had always been a slightly spongy feeling to the unused parts of our Adirondack front porch, a smell of things rotting and sagging. “This is camping”, the Baker Camp manager had warned me on the phone, as if accustomed to complaints from overnighters not used to roughing it. And she’s half right. But unlike sleeping in a tent, you have electricity, a porch, a door that latches, windows that close, lights that work, and best of all, that roof over your head in case it rains.

A little beach (closed after Labor Day) with a single lifeguard chair is set beneath the pines, with the cabins scattered along the slope of the hillside behind it. Standard cabins were built 18′ x 18′, and they each have a porch that overlooks the lake. It’s all at a very small scale, even the great dining hall that serves meals during the summer season. Until next year, that’s closed, too.

To be sure, there are things that should be repaired. The shredded roofs, the lilting stilted porches of some of the cabins, the tall weeds sprouting through the floors of abandoned sailboats remind you that nature is always pressing in and reclaiming what’s hers faster than the caretakers can fix it. The mature trees — pines, cedars, oak along the shore and a dogwood here and there — on the grounds are beautiful, but the Japanese barberry at their feet should be taken out. It’s everywhere.

It’s not as quiet as you might imagine, this late summer evening, nobody around. A woodpecker is pounding the pine tree above me. Fish inch toward the sandy shore and splash around a little bit. A catbird continues in the trees. So do crows, crickets, goldfinches, tanagers late to fly south, and the grating katydids that come out after dark to drown out the crickets.

At night, I built a fire right on the beach, scrounging in the pine needles for kindling and boughs. I brought down my laptop, a bottle of wine, a radio to listen to the Mets make their dubious late-season run. Stranger things have happened to my Mets, and watching the fishermen cast out, I pulled up memories of other September slim chances: fishing on Long Island Sound with my brother and son, a pizza between us and the Mets game on the radio. We can dream, and in September, I’m afraid we do.

Fisherman in metal boats appeared on the water, one or two to a boat, the echo of water under their hulls reaching me on the beach. Then, a canoe, carrying two paddlers from the nearby ACA camp, came close to shore to say hello. It was a nice time of night to be out on the lake, they told me. They reported that I wasn’t alone: a herd of deer was grazing on the shore around the corner. I watched them cross the lake, heading towards their own evening.

There is that moment just before darkness comes down completely, when it’s suddenly as quiet as it’s going to get. No cars, no voices, no low voices on the water. The sound of the fire, the crickets, and a far-away airplane, before the sweetness of the cricket sound is replaced with the sawing, ratchety-sounding katydids. I was half-tempted to throw my sleeping bag on the sand near the fire ring, and just spend the night outside. I knew it was probably against the rules, but I was alone, after all. I’m not sure who would have minded.

The Details:

The dining hall is closed. You’ll have to bring your own bedding, your own food, and if you need to cook for a group, you should bring a grill, or cook on one of the fire rings down near the beach. I kept it primitive, but stylish: a block of cheese, a bottle of wine, a chicken salad, a french press with coffee, some chocolate afterwards. For breakfast, I boiled water on a Jetboil and made a big bowl of oatmeal, and opened a package of Scottish salmon.

And the bathroom situation can be tricky if you need to go in the night. There are a couple communal bathrooms for the entire camp, with flush toilets and showers, stall-style.

You can rent boats for $15.00 an hour, or for the whole day ($70.00). However, you must show up before 5:15 pm to rent.

Baker Camp is not for everyone. If you have camped happily in a lean-to, this is a step up. I found the bed — a cot — comfortable enough, but I wished I’d brought a pillow. Other than that, I love these little rustic cabins.

I paid $60.00 — by check, as they don’t take credit cards — for a two-room cabin (standard) with three beds. There are large cabins available for bigger groups, and they have interior fireplaces. Check in hours after Labor Day are when you arrive, with check-out being 24 hours later if you’re staying for one day.

What I brought:

Sleeping bag;

Jetboil;

Starbucks “Via” instant coffee packs;

A bottle of wine;

A cup and a mug;

Instant oatmeal;

Two LED lanterns to hang on the porch at night;

My computer and cell phone (there was Verizon reception in my cabin);

Camera

What I wished I’d brought:

A pillow;

Another blanket;

Mets hat.

A large-ish water dispenser.

I drove through Harriman & the cabins & even the tent camping area about a month ago. It’s a beautiful area. And now that I read your blog I really want to rent a cabin & enjoy all the nature & solitude.

Thanks, Susan. I hope you get a nice day for it. I’m sure you could get almost any cabin with very short notice. It’s really, really pretty up there. Hope you go.

Suzy, I tried calling the camp, but they didn’t answer. I’m trying to find out when the camping season is over. I was hoping to go October 24th-25th, but wasn’t sure when they close. any clue? Thanks in advance. BTW, I love this blog, I’ve been dreaming of renting this cabin ever since I read your blog, and saw your pictures. It looks like just what the doctor ordered!

My Uncle Bob Wynns ran the Camp I was orphaned at 12 and he and Aunt Charlene took me in. I lived and worked at the camp when I was a teenager. I was a dishwasher and bus boy. Later the fact I started to pay social security when I was 12 helped my social security pay!

LOVE LOVE LOVE your pictures… go there almost every year ..thanks for posting them.

Thank you, Cindy. It looks like one of those places you come to year after year. I bet it’s fun when that big dining hall is open, and everybody heads up for dinner.

the owner/manager Dick and family are nice people – the place needs attention but the “Park” is not willing to put much $ into it…that’s good because it leaves it as described…great lake (been there for over sixty years) and the rustic thing keeps those away that should be away…

next time listen for the loons…

don u.

Thank you for the comment, Don! I really love the caretakers. Dick was feeding the deer when I got there, and his wife sat on the steps and told me about them. Dick told me how to get to the top of Brundige Hill, to the water towers and the old tennis court, and how to avoid snakes. A super couple. Do you think it’s too early for the loons? I was up at 5 but didn’t hear them.

Nice post! I’ve spent plenty of time in the ACA Camp on Lake Sebago, back when I was an active member of one of the canoe clubs that has a cabin there. They also have private cabins for rent there to ACA members. I agree the cabins, with electric lights and propane cooking facilities, and showers and rest room facilities down the path, are sometimes the perfect compromise between roughing it via backpack, or being limited to visiting the park for a day trip.

Hi Jamie. That’s what I love. I’m right in the middle of “roughing it” and “day tripping”, and I couldn’t have put it better myself. Perfect Compromise.

In your writeup you mentioned the ADK camp and the ACA camp. However you did not mention the public camp.

The public camp is directly across the lake from Baker Camp. Facilities are roughly the same as at Baker Camp with the price about the same.

I just returned home after a week at the camp. We have been staying there for over 50 years ever since NYU gave up the camp. After the weekend there was only one cabin besides ours rented.

You certainly describe the lake in the off season very well.

Hi Bob — thanks for the note. I was thinking of doing a similar review of Sebago Cabin Camp — I don’t know if it’s the same in terms of amenities and friendliness. Do you have any experience there?

(Or maybe that’s the camp you’re referring to in your comment).

Thanks!

Hi Suzy–

Thanks so much for posting this! I would love to plan a midweek escape to Baker Camp as you describe.

A question for you: Do you know whether it’s possible to rent a kayak or canoe as a day-visitor to Baker Camp or do you have to be a cabin-renter?

Rachel

Day visitor is fine..

Hi Rachel: Sorry, I just saw your comment! Yes, you can rent a boat even if you’re not a cabin-renter. They rent out boats up to 5:00 pm, as all boats have to be in by 6 pm. Thanks!

Thanks Cindy and Suzy–

I will give it a try! I’ve always wanted to kayak on Lake Sebago, and renting at Baker Camp seems like the way to go. As an apartment-dweller, owning one is simply not an option. I don’t even think I could squeeze in an inflatable! 😉

Suzy who took your pictures?? and with what ..they are so perfect.. I have your story “pinned” on our facebook page.. This way the girls can see what they’ve missed.. Can’t wait to go back next year.

Hi Cindy — Thanks for that! I took the pictures with a Canon Mark IV (I’m a news/sports photographer in my “real” life). Thanks for pinning! I think this would be a great place for a bunch of girls (especially if one has a desperate aversion to roughing it, haha!)

Sounds like new owners. Where are they from?

Turned out that Rae’s husband, Mike Hirsh, was a classmate of mine at Wm. Cullen Bryant HS in Astoria, Long Island. We never met; not surprising as our class was so big there were 3 graduation ceremonies!

Hi Lee — are you sure they’re new owners? I’m pretty sure their names are Dick and Rae…but someone will correct me here. :0)

Not new owners and Lee should know that..she was there in 2010…

Sounds like a perfect getaway for some perfect end of summer relaxing time. I am glad you enjoyed your solitude in the forests of Harriman State Park Suzy! 🙂

P.S. did you bring your bear spray??? 🙂

I did bring it, Nam. Actually it’s always hanging off my keychain! I’ve only had to use it once. I was transporting a pit bull who was being given up by his owner because he was too — ahem — amorous. I tried to take him for a hike and he would not leave me alone! I mean, not for a second. So I lightly spritzed the air up above his head, and as the pepper spray gently drifted down over both of us, he stopped. For about 15 seconds! Ah well. He’s in a good, responsible home now, and he was, of course, fixed.

Enjoy the end of summer!

PS: A couple days ago, I hiked the Menomine trail to Stockbridge, and saw exactly where you guys set up camp. And the burned rock face! That’s such a nice area; I never really considered the other places to set up camp surrounding the rock shelter. Very nice.

All you really need is a Bear Scare..lol

What’s that, Cindy? What’s a Bear Scare?

It’s something that we were given at Girl Scout camp,,(Camp Quidnunc, Harriman) It is a thin leather strip , size of a shoelace.. and it has knots tied in it.. Two of our Minnasota conselors brought them to camp . They called them Bear Scares… If you look it up on the net you can read the sotries about them.. I replied as a joke.. because everyone asks ” does it work?” and which we reply..”haven’t run into a bear yet” lol… We wore ours until they fell off.. Sorry if you thought it was legit..

Haha — Cindy, if it didn’t involve plundering the earth’s resources, I’d suggest making them afresh! Funny idea. :0)

how does one go about renting a cabin? This place seems so beautiful and would be perfect for a simple ceremony and then bbq for a very small wedding!

Sami, you just have to give them a call. I know they have weddings there — you just have to understand that it’s very rustic, but this has appeal for a very different kind of wedding! They also have a “great hall” that’s used for the ceremony, and probably reception, but I’m sure you couild also cook on the beach as well.

If I were planning a wedding — a small one — I would definitely consider this place. Very “Pinteresty”!

i been going there for about 40 years its beatifuail used to be run by two banks in NY i love it there. the manager is richard and rae hirsh

Dick & Raelyn Hirsch became Managers of Baker Camp back in the early 1970’s & they had either 2 or 3 children. Prior to that Mr. & Mrs. Wynn, originally from Texas, were the managers. The camp, for the use of the employees of four large New York Banks, was built with a gift of $100,000 by George F. Baker on Lake Sebago, Harriman State Park, and was open for spring vacations in May 1927 or 1928. In the 1960’s Bankers Trust(BT) company and United States Trust Company jointly operated Baker Camp for their employees and absorbed well over half the cost of operating Baker Camp, thereby keeping rates charged their employees very low. Rates included lodging in your own rustic ‘summer’ cabin, three meals served daily in the dining hall and use of recreational facilities. Went there from 1956-1976.

Nice discussion on BC. I went there from 1954-1972 so we might have run in to each other then—-after all, it was a small place! Dick and Raelyn hired me in 1968 for summer work while in school and I returned for four more years.

Baker Camp was originally opened by four banks for their employees. I believe they were Bankers Trust, U. S. Trust,

Bank of N. Y. and one other I can’t remember. My family went there every summer for two weeks as long as I can remember. Dad worked for Bankers Trust. My sister and I made many friends. There were two kinds of cabins – the ones on the hill with no indoor plumbing – there were outhouses – and each cabin had buckets just in case – no windows just canvas that you pulled shut at night. Then we had the Officers’ cabins up the hill – they had indoor plumbing, beautiful stone fireplaces and three or four bedrooms. We never got them until the Wynns took over – I believe in the early 40s – and my parents and their friends had cocktail hour before dinner each night. We youngsters were already up at the Canteen playing ping pong, etc. until the bell was wrung to get to the dining hall. I caught my first large mouth bass and Clem the chef cooked it and made a great presentation. Do you remember his cinnamon buns?

Do you remember the waiter’s cabin? In the beginning we had no car so we took the train up and and were met at the station (hence the name station wagon) which was wooden.

I kept in touch with many of my summer friends but most are long gone now. My last summer there was in 1954 when I graduated from high school. Delayed my job at J. P . Morgan until August so I would not miss my last time there. Almost lost the job because they did not think that was a good excuse but when I explained further the Personnel Director knew about the Camp and I had the job.

This is Carolyn Brass. I’m looking forward to keeping in touch with anyone interested in revisiting Baker Camp memoirs please please keep in touch

This is Carolyn Brass. I’m looking forward to keeping in touch with anyone interested in revisiting Baker Camp memoirs please please keep in touch

Hi! My dad worked for Banker’s Trust for decades but I only got to go there once, as a little kid, but remember it vividly and fondly. My guess is I was there in the summer of 1971. My older brother had gone back in the early 1960s, and we both remember the bell calling everyone to our meals. Take care, and thanks for posting.

Carolyn Brass?!? OMG! How are you and how can I get in touch? We have a Baker Camp memories page on Facebook. I still see Brian Banks all the time! : )

I worked for USTrust in the 1970’s and a bunch of us happened upon Baker Camp as kind of a silly and fun thing to do. We were all “city” girls, and knew nothing about camping. Well, it turned out that we had some of the best times of our lives at Baker Camp. We would go up on Friday night and leave on Sunday after lunch. If I remember correctly, the whole cost of the weekend was $27 per person, which included all meals which were served in a Dining Room and very delicious. We fished, went rowing on the lake and generally have so much fun. We would plan ‘theme’ weekends, like Christmas in July We kept going until the last one of us stopped working at USTrust.

Enjoyed reading this. Thanks Suzy

This is beautifully written. Sums up this hidden gem. It’s true I’ve heard many people complain about this place. I feel sorry for those people that can’t find the beauty in it. My family has been going for the past 4 years. Although we haven’t gone that late in the summer, we managed to go during the less busy summer weeks checking in mid week to have some privacy and peace before the weekend rush. We went to book our trip for this summer but to our dismay have not been able to contact anyone and discovered from Rae’s website that the camp is permanently closed. I have been scouring the internet for more info but to no avail. I’m glad I stumbled onto your blog. Reading brought back a great visual to a beloved place. Hopefully I can find out what happened and that the place reopens.

Would you have any other suggestions of nearby places that are similar to what Baker has to offer?

Hi! I’d say give the Outdoor Center at Harriman (the AMC campsite) a try. There are cabins, tent sites and lean-tos that are refurbished old campsites. Breakneck Pond is beautiful, and you’ll be able to have some good food with company if you choose, or get any camp supplies you might need. (And if you’ve never been to an AMC camp, you should give it a try! )

Accidently stumbled on to your blog.I vacation at Baker Camp from 1958-1966. Then was a bus boy, waiter and head waiter over 1966-1969.I was a great place to work, no parents, college guys,beer, pot ,it was truly the greatest time of my young life.

Baker Camp Solitude, Not Quite Fall – | My Harriman

[url=http://www.fitflopsale-uk.com]fitflop UK[/url]

Did Baker Camp close??

My dad also worked for Bankers Trust. My parents and we four kids would go every summer for two weeks, sometimes three. 1966 – 1976. Getting out of the hot city for a couple of weeks in the summer was the best. The same families would be there year after year so you would always see your “Baker Camp friends”. What great memories! The canteen, teather ball, fishing, row boating, the tiny frogs and tadpoles, walking the long drive to the entrance with your friends, who got to ring the bell for the next meal at the dining hall! We all learned to swim there as well. Each night there was something to do, arcade night, square dancing, etc. They had excursions for the kids also and would take us to the roller skating rink and horseback riding. Those were some really great times! So sad that it’s closed. The last time I was there was about 26 years ago and I’d like to go and revisit those memories.

Yes our dad worked there too. We went for several dinners for 1 weeks. If I remember correctly there was an “Indian head rock “ on the main drive into the campgrounds.

Very interesting article. My grandfather was a Bankers Trust employee so our family spent many a summer vacation at Bakers camp. My last time there , it was probably 1964-65 when I was 9-10. I remember waking early to be the first out to ring the bell, when instructed, for morning breakfast. It’s also where I got my lifetime fish story. My older brothers wouldn’t take me fishing with them in the early morning. They told me to catch the big bass that lived under the dock. Well I’m upset and fishing off the dock when I caught a little sunny. As I’m reeling in my big catch out comes that big bass and eats my little sunny. I yank the big fish out and it falls off the hook onto the dock. I quicky scoop him up and put him in my bucket. My Dad had my big catch for dinner that night as the camp chef prepared it for him. Thank You for bringing back fond memories!

How can I make book the cabins

My father worked for Bankers Trust and we spent many enjoyable summers there. We would go for two weeks every summer from 1957 through 1964.

I formed many fond memories there and learned to swim and enjoyed hiking the various trails. Out fishing in a rowboat at 6AM…the lake was like a sheet of glass and the solitude was amazing.

We went for a few years in the early ’70s when my Dad worked for Bankers Trust. At the time, I was jealous of my schoolmates going to Disneyland, but now I wouldn’t trade those memories for anything.

The Appalachian Mountain Club is in the process of rehabilitating Baker Camp but the task is huge and will take a number of years. In the meantime, AMC’s Corman Center is a wonderful alternative.

I remember going therein the late 60’s with my family. My dad worked for U.S Trust Company. Each summer we would go with other families my parents knew. When i was 14, i started working there,as a dishwasher, then became a waiter. Worked there every year in high school,in the summer. Weekends in May,and full time after school was out. Many great memories, and good friends. My family went back some years ago,and our name is carved above the door on one of the larger cabins on the hill, you’ll have to go to find out which one..lol Baker Camp will always be in my heart.

My family of 6 stayed at the Camp in a cabin during the Autumn of 1964 or 1965. The ages of us girls were 18,15,13 & 12. I was the 13yr old. There was still activity at the Main Dining Hall – meals & activities for teenagers – dances etc. We had a fabulous time.

I was raised at the camp after my mom died of cancer and left me an orphan. My Uncle Bob Wynns sort of looked after me and I lived and worked as a dishwasher and buss boy. I loved living in the woods!