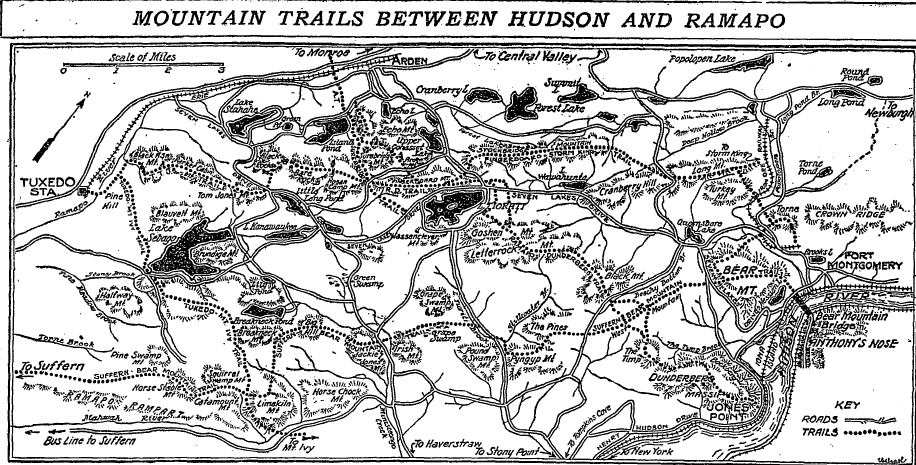

Map of newly-opened Harriman Park trails, from Raymond Torrey’s 1926 article in The New York Times. Download the PDF of the full article using the link below.

Raymond Torrey’s Description of a Trail Built to Last

I woke up this morning thinking it would be easy to throw the dogs in the car and do a five-mile trek through Harriman State Park. And then I woke up again, this time from the dream I had of springtime, and having young dogs capable of hiking for five miles through the unfurling skunk cabbage and moss turning green under oak and ash.

Because I can’t wait for spring — though my dogs will probably be incapable, by then, of getting in or out of the car — dreams sometimes taunt me.

So it was like opening a little gift from the past this morning, to come across this article in the May 2 edition of the New York Times by Raymond Torrey, that chronicler of the early days of the park’s newly-built trails. I’d posted one of his articles before — about the Suffern-Bear Mountain trail — but this time I’d found Torrey’s description of the Ramapo-Dunderberg trail.

In 1926, after five years of scouting and clearing, after the “Elephant Squad”, with hatchets and pruners, cleared the trails for New York City backpackers and day-hikers, 100 miles of trails through the Harriman woods were opened to the public.

To read the Times’ article from start to finish is to take a little pretend hike on this classic Harriman trail when it’s too cold for hiking to be enjoyable. You follow Torrey’s descriptions with a map in hand, up one side of a mountain and down the next, crossing woods roads that hadn’t yet returned to woods, following the R-D to its end at Jones Point.

After nearly 100 years, not much has changed on the trails. But it’s the little things, the details, that can surprise: markers no longer made of iron or copper, shelters that have disappeared.

Sometimes he’ll use an unfamiliar name for a road whose name-change makes logical sense (The Old Continental Road became, at some point, Victory Trail, and he notes that it was a military route of the Revolution, “echoing the tread of American feet”).

Or, sometimes he’ll refer to a feature that you’d never noticed before:

“About 150 yards northeast of the old road is one of the most notable geological curiosities of the Harriman Park, a large, beautifully smoothed pothole, in hard granite, site of an abandoned waterfall, now a mile from any stream.”

Where is that?*

Like my dogs, most of us will (under the best circumstances) grow old, and the day will come when we’re incapable of getting in or out of the car. Even ol’ Raymond Torrey, who lavished his craft on these painstaking descriptions of individual trails, would have finally hiked his last hike.

I think of getting to that last hike myself, and trying to eke one more out of my legs. In my mind, to stave off the inevitable, I’ve concocted a hybrid all-terrain wheelchair, a pair of ridiculously rugged crutches, a miniature hiking-horse (who is adorable). But I think Raymond Torrey has done most of the work for me, because maybe in the end you just surrender gracefully the things of youth — hiking included — and remember. Read, and remember.

Download the article PDF:

Torrey’s description of the Ramapo-Dunderberg trail.

Arrived in Tuxedo after taking the train up from Manhattan. It was a beautiful fall day, and I set out on the Ramapo Dunderberg trail. I was carrying quite a bit of weight, so the trekking poles I carried were a must. I took the trail North for about 4 hours. I passed a beautiful waterfall and had great views from the section atop Black Ash Mountain. I reached the beginning of the White Cross trail, and turned South. I took White Cross until it intersected White Bar Trail, which I followed down to the Dutch Doctor lean-to. I set up a solo tent, purified some water at the brook nearby, and started gathering firewood. I ate next to a small fire as the sunset. Prior to arriving at the shelter I passed 6 hikers- 4 of them within 20 minutes of entering the park. The next day I took the Tuxedo-Mt. Ivy trail back to the station, and was back in NYC by sunset. Great hike.