Not on the Map

For the weekend, at least, a kind of summer visited downstate New York. Saturday dawned cloudless and crystalline, with just enough of a chill to make you wonder if you’d need a sweatshirt on the trails. But by the time we got to Harriman and parked the car it was edging 65 degrees and promising 75.

The parking lots we’d passed were full, and so it seemed we’d come through another winter and emerged into Harriman’s Opening Day, the start of the summer hiking season. We headed for The Quiet Corner.

We’d made the drive with the windows down, jugs of Gatorade sloshing blasphemously in the back seat. We’d swung north onto fabled-but-modest Route 6, America’s longest continuous highway, a coast-to-coast uncertain run between nowhere and nowhere that passes right through Harriman.

The parking area on Route 6, the one we used for our hike, is a pullout that serves the fishermen using the lakes Massawippa, Barnes, and Te Ata (GPS: 41.32273 N, 74.08140 W). Today, though, on Harriman’s busiest day, we were alone.

“The Quiet Corner” is that northwest section of the park that’s nearly severed from the rest of Harriman by Route 6, and surrounded on all other sides by the United States Military’s forbidden lands. You’ll only find the blazes of the Long Path up here, so crowds, too, are rare. The trails here skirt lakes, abandoned summer camps, and swamps, and you can use them in a configuration with the other marked trails to form loop hikes back to your car.

I’ve been wanting to visit deep Brooks Hollow for as long as I’ve had a Harriman map, and so was happy to hear of an old woods road running from Route 6 — just east of Lake Massawippa — into the hollow. You can park in the lot near Barnes Lake, and then walk along 6 until you reach the gate (it’s labeled “restricted”, but I think that applies to cars).

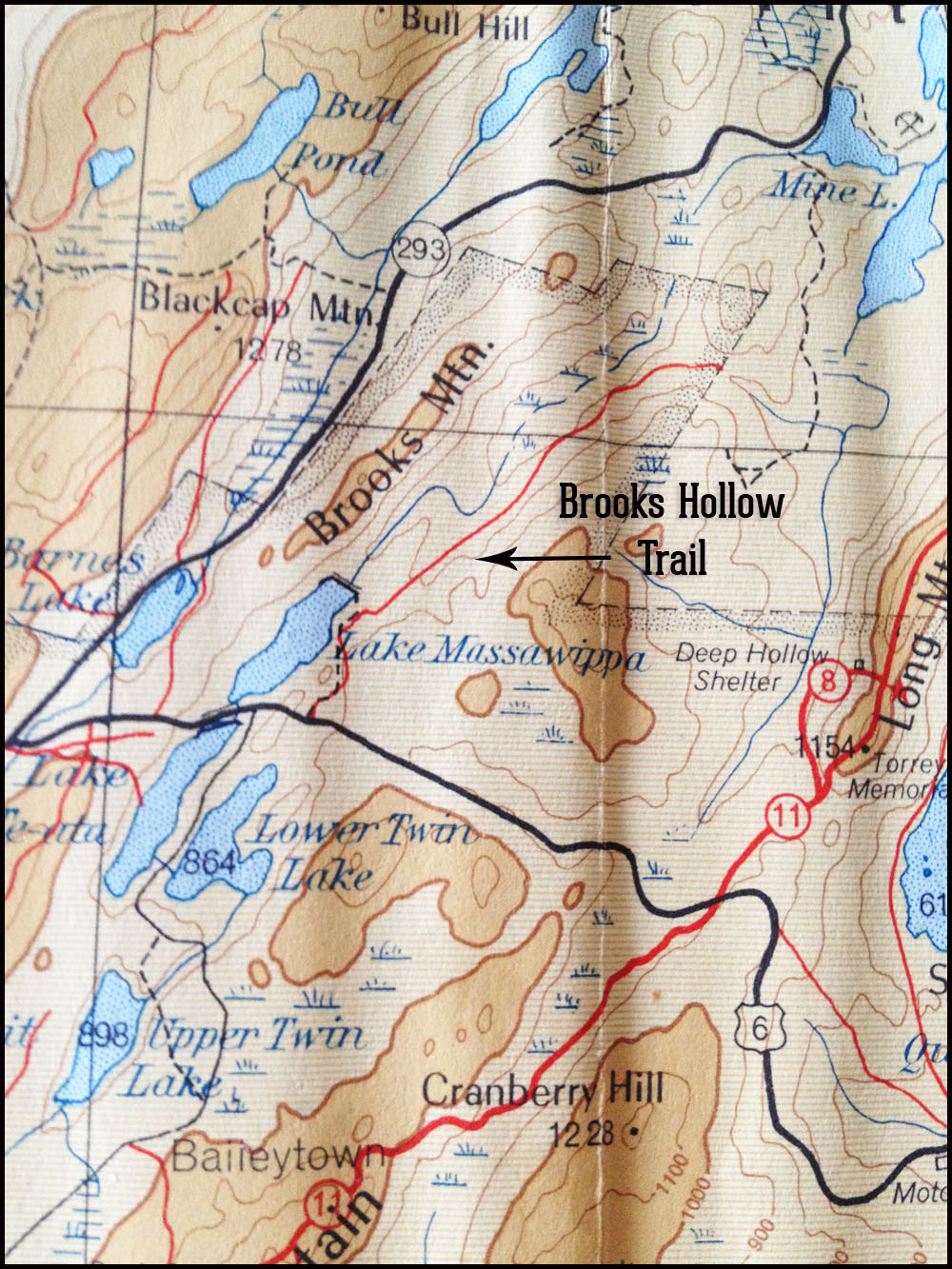

Hiker’s map, 1953, showing Brooks Hollow Trail. This map is from the old New York Walk Book, by Raymond Torrey. You can pick one up on Ebay, usually, and most come with the map still tucked in the back jacket.

Following a barely-paved and rutted old road, you’ll parallel the shore of the lake to the ruins of an old camp. The caved-in and floorless, roofless structures are dangerous now (I’d hate to be there at night), but you’ll find a gentle grassy slope to a small swimming area, with a fire ring nearby, stuffed to overflowing with charcoal ash. And Massawippa (try not saying that word over and over again on your hike) is peaceful, despite the distant roar of cars speeding towards somewhere else.

On Saturday, we broke out lunch on this slope. Cheese, crackers, a little bottle of wine, some dried fruit made a picnic as a single duck insisted on his ownership of Massawippa.

Harriman is full of such un-named, unmarked trails, the historic remnants of a lost way of life shared by farmers and miners and later, campers. In his “The New York Walk Book”, Raymond Torrey wrote in 1932, “In the early years of the park the walker had many dirt roads and miles upon miles of wood roads built by the iron workers to follow, or, like William Thompson Howell, he could choose his own way through the thickening woodland according to the topography, his taste, and his compass.”

The woods roads and unmarked trails offer you a chance to do both. It really is a pleasure to find (and hike) roads taken by the charcoal-burners, the iron miners, the farmers and townspeople of long-vanished mountain hamlets. Because many of the old woods roads were built for utilitarian purposes, they follow comfortable routes along valley floors and streams, and so don’t lead to many vantage points.

But you take them for a different purpose, I think. Call it the answer to a curiosity, a need to explore, to see where a road goes through the forest. An uncomplicated thing, as simple as the desire to follow the suggestion of a road.

The road continues past the old camp, its blacktop soon yielding to a soft, mossy trail. We began to hear the rush of the outlet stream of Massawippa, high and frisky with the early spring run-off, and by the time we reached it, it was clear we’d need to straddle something to cross. Just on the other side of the stream is the Long Path, and beyond that — you’ll want to search a little to find it, but it’s visible — the continuation of Brooks Hollow Trail.

That a half millennium of change could leave both the forest and its network of old trails intact is a wonder. It’s a wonder, too, that such an out-of-the-way unmarked trail could still push back against the gathering woods. Glistening beech saplings, no wider than a finger but taller than me, grew up through the road’s floor. But here and there, deadfall was split neatly by a chain saw to let hikers through. Someone is using the trail, yes, but more remarkably, someone is maintaining it.

The fun of following the old roads is, I think, in detecting them, picking their static remnants out of a dynamic landscape. You train your eyes, in a way, to pick up level stretches of land, or a rocky road wall, or the way a crowd of beech saplings invades the space all at once. Look for the easiest route through the woods — no slopes or boulders to climb — and that’s probably the way of the old woods road.

We hiked along old Brooks Hollow Trail — or what is left of it — up above the “hollow” itself. Brooks Hollow shows on the modern map as a long and narrow pond between Brooks Mountain to the west, and Howell Mountain to the east. In early to late spring, it’s full of water, but I wonder if it would be dry by August. Ducks, geese and spring peepers, a large flock of twittering bluebirds, plus the occasional overhead jet, made the only sounds of that part of the woods.

The pond that sits in Brooks Hollow is clearly the work of a dastardly band of beaver, probably descended from the six pairs of beaver that were given to the park in 1920 by the State Conservation Department and release in Beechy Bottom:

“In ten years they had spread over the park area and into private lands, building an estimated forty ponds, damming streams at many points in their courses and even raising the levels of pre-existing waterbodies dammed by man. These provided real benefits in establishing breeding-places for fish and waterfowl and in regulating the run-off of the small streams liable to dry up in times of drought, but they also drowned out wood roads, meadows, and even considerable stands of trees.” (Raymond Torrey, “New York Walk Book”)

You can continue along the trail to the boundary of Harriman Park, where the road continued into West Point lands, an indefatigable no-go for hikers. We retraced our steps, back to the Long Path; we took a right up to the top of Brooks Mountain, along the ridge, and past a framed memorial to Copper, a steadfast trail dog who was evidently a fan of the trails and who passed away in 2013. Good old Copper. And then back down.

If You’re Taking the Unmarked Trails, Some General Tips:

- Make sure you have a contour map, a compass, and a phone. Know how to navigate.

- Many unmarked woods roads have their hazards: stony “ankle-breaker” surfaces, deadfall across the trail, missing cairns.

- Unmarked trails that are utilitarian are often not the best routes to vantage points or sight-seeing areas, but they’re fun to take anyway.

- Woods roads tend to stick to the valleys (not the ridges) so they’re nice for hot summer days.

- If you’re using a phone for navigating, bring a back-up battery.

- The book, “Harriman Trails”, by William J. Myles and Daniel Chazin, has more about these unmarked routes, including history.

- You can also pick up an old copy of “New York Walk Book” on Ebay. The first edition came out in 1932, and it’s been revised, but you can always find an antique, most of them with the original trail map still contained in the book’s jacket pocket. This is one of my favorite Harriman (and surrounding area) reads.

- If you’re looking at the map, and wishing there was a shortcut from your trail to a well-established trail, keep you eye out. Often these shortcuts have already been made but not mapped, and you can follow sets of cairns to the trail. DON’T do this is your not a skilled navigator.

- Naturally: the NYNJTC trail map is a great place to start exploring these trails.

The Brooks Hollow Trail is one of my favorite “secret” trails. Although I’ve hiked it many times, north to south from its intersection with the Long Path, it’s always a challenge to pick up that trail from its northern terminus. There is no discernible treadway and no cairns at its extreme north end. I’ve blundered around more than once before finding the trail.

Blundering around = Being mistaken for Bigfoot = Harry Man State Park. There are worse fates! I wonder if it’s frowned upon to start cairns…

I think that cairns are both helpful and evil. Minimizing alternate bush wacking routes that become de facto trails should be part of any responsible hiker’s consciousness. Otherwise you end up with a place like Blue Mountain County park. Just my opinion.

Thank you, Suzy. Your dispatches never fail to stir my wanderlust. After reading your account about your visit to the Brooks Hollow Trail, I’ll have to add it to this year’s “To Do(and savor)List”. It sounds like a wonderful place to visit when the crowds are out in full force. Thanks for the Ebay/”New York Walk Book” tip. I snatched one up, and can’t wait to see the old map.

Thank you so much, Robert! And I’m glad you got the Walk Book. The map doesn’t have the thruway, or the Parkway — you’ll love it!

Well, the book arrived quickly. On the title page, under a beautiful woodcut of a narrowing path, was line from a Rudyard Kipling poem titled, “The Feet of the Young Men”. Here’s a small excerpt that seems appropriate as the weather warms, and the trails beckon:

So for one the wet sail arching through the rainbow round the bow,

And for one the creak of snow-shoes on the crust;

And for one the lakeside lilies where the bull-moose waits the cow,

And for one the mule-train coughing in the dust.

Who hath smelt wood-smoke at twilight? Who hath heard the birch-log burning?

Who is quick to read the noises of the night?

Let him follow with the others, for the Young Men’s feet are turning

To the camps of proved desire and known delight!

Let him go—go—go away from here!

On the other side the world he’s overdue.

’Send your road is clear before you when the old Springfret comes o’er you,

And the Red Gods call for you!

Robert, this reminds me of another poem, one carved by CCC’ers on a header of a wood-and-stone pavilion in Fahnestock park. It overlooks Pelton Pond. Do you know the one?

I’m afraid I’m not familiar with the CCCer’s poem at Fahnstock, Suzy. In deference to the writers of the verse, who’ve probably joined the Ocean’s Choir by now, I’ll ask that you not post it in order to give me some time to first see the carved words with my very own eyes. The CCCers deserve respect for the honorable work they did in the park 80 years ago. Besides, for me, a visit to Fahnstock is long overdue. Thanks for the tip. I’ll report back soon…

Won’t you miss it all,

the smell of the pine,

The clean-swept skies at dawn,

the million stars of a summer night,

the thrill to a robin’s song?

Will you dream again of wooded lanes,

Richly bathed in morning dew,

of fragrant bowers where tiny flowers

present themselves to view?

Won’t you yearn again for the solitude,

The peace of mind and heart,

the quiet splendor of lofty peaks,

of their beauty set apart?

Oh,yes, you’re sure to miss all of this,

but in leaving you may take away,

memories of all the heart holds dear,

the dreams of yesterday.

That’s the one! I like the poem, though I think it loses something at the end. Thanks for posting that!

That was written by C.C.C. enrolee Richard Toomy from West Campton, NY approximately 80 years ago.

Sorry, West Campton, NH

My brother-in-law and I explored this walk, unblazed and with many side trails. The parking lot for Lake Massa-wippa (did this name originate in the South) is completely obscured by signs on route 6 for Route 293, giving some hint of the priority given hikers. Unfortunately, what would otherwise be a quiet walk about a decaying former camp is punctuated by road noise from Rt.6, especially the continuous whine from the rumble strip over the bridge of the inlet to the lake, and, then, on a Sunday, the sonic blasts of artillery blasts from nearby West Point Reservation. I certainly hope those cadets have good aim or vigilant supervisors.

Wow I thought it was the girls camp there Camp TeAta – Girl Scout camp I went to and worked at for several years. It’s off rt 6 E marked by a chain across for no trespassing albeit danger in the condition of buildings. The pic looks like the arts and crafts bldg.

That “abandoned camp” on Lake Massawippa was Camp Orenda of the now defunct Boys Athletic League serving mostly disadvantaged NYC kids.

I worked there several summers in the 1970s and enjoyed taking the campers on overnight hikes all over Harriman dining on army surplus food and sleeping in woolen sacks. Sad to see the deterioration.